(N.B. This article may be difficult for the visually impaired/those using screen-readers due to the use of images of text. I apologise, and am working to improve this.)

When I sat down to read The Wind in the Willows for this week, I did so under the impression that I was familiar with this story, having read and watched versions of it with all three of my children. I found, though, that reading something to your child is a very different thing to a critical close-reading of something, and I had a couple of realisations.

The first of these was in relation to the influence of the Romantic poets on the extensive descriptions of nature, the landscape, and the river in the book, which begin in the first chapter as Mole leaves his home and begins to explore. These descriptions have many elements of ‘the picturesque’[1], and Tess Cosslett points out in ‘Arcadias?’ [2] that the text is ‘full of allusions to the romantic poets’ and ‘deploys [a] romanticised view of nature’ (2006, p.151). This can be seen in many long passages, such as this one from Chapter Three ‘The Wild Wood’ which is full of anthropomorphic descriptions of plants and scenery reminiscent of Wordsworth and Keats:

The Romantics’ influence is also evident in the reactions of the animals, particularly Rat and Mole, to nature and the landscape. In Chapter One, ‘The Riverbank’, for example, Mole’s breathless ‘O my! O my! O my!’ is clearly an invocation of the Romantic concept of ‘the sublime’, where the beauty of the natural world is such that one’s conscious self is too awe-inspired for rational thought and response must come instead from one’s inner spirit.

This veneration of ‘nature’ is linked to my other realisation about The Wind in the Willows. In an essay called ‘The Blue Guide’[1], Roland Barthes links ‘the cult of nature’ with the ‘bourgeois’ promoting of the mountains’ and ‘Protestant morality’ – i.e. enjoyment of the natural world is very much a middle-class pursuit. The Wind in the Willows vehemently emphasises this in several ways.

First in the

sense of ownership of The River which the Rat shows in the first chapter.

Having described it in all seasons, he claims that the river ‘bank is so

crowded nowadays that many people are moving away altogether. O no it isn’t

what it used to be, at all’ which can be seen as a forerunner of the ‘NIMBYism’

of the middle-classes [2].

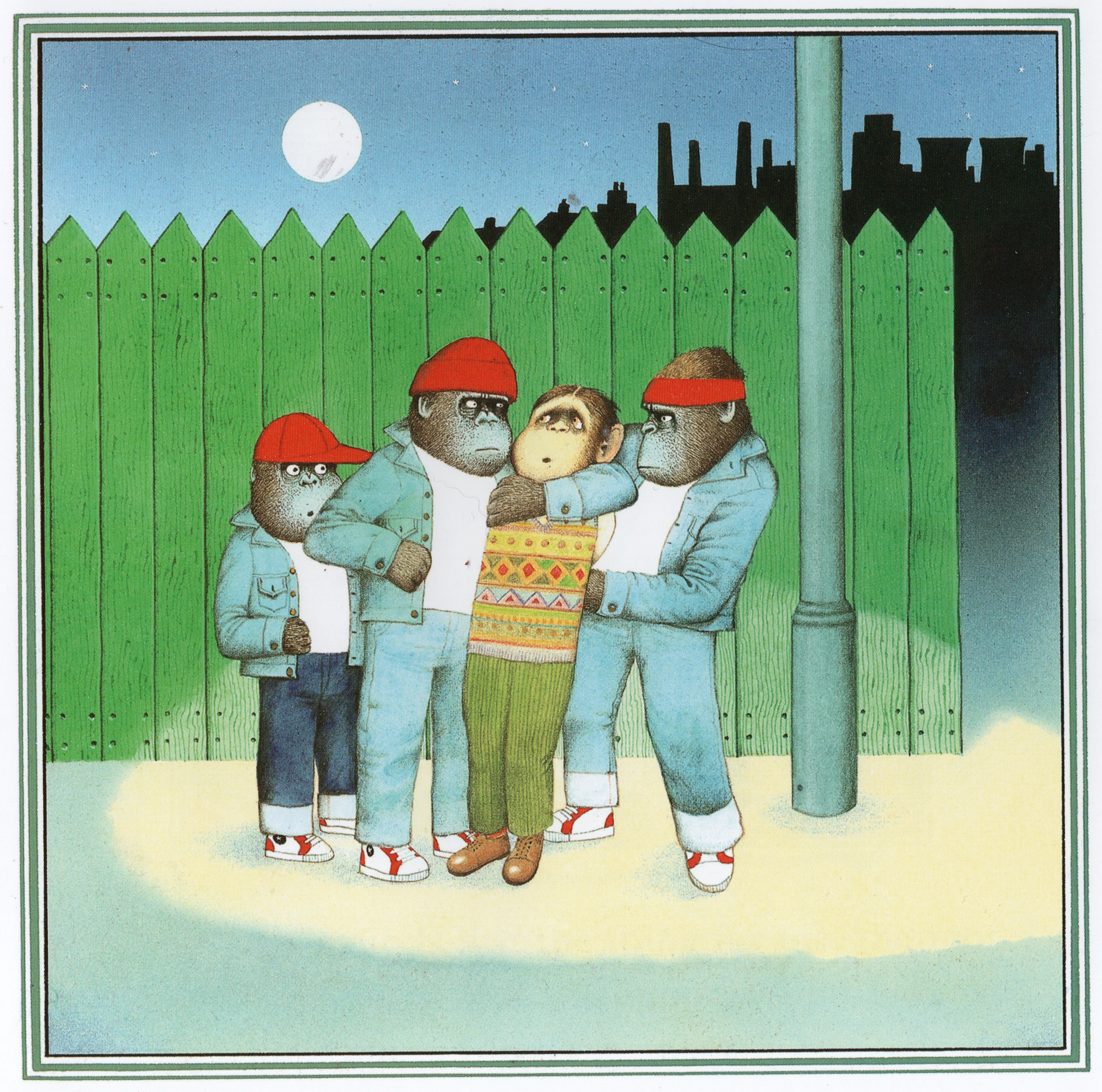

Much more obvious though is the oppression of the working-classes, represented

by the residents of the Wild Wood, and the denigration of the aristocracy

represented by Toad. Further on in Chapter One, Mole asks about the Wild Wood.

This presents the Wild Wood as a sort of slum, ‘a bad area’ where decent people – ‘we river-bankers’- don’t go, and where the residents ‘break out sometimes’. Further into the story Mole becomes lost in the Wild Wood and feels threatened and terrified when being observed by these ‘untrustworthy’ residents, although he is never actually threatened by them, other than in his imagination. At the very end, after ‘the uprising’ of the weasels, stoats and ferrets, we come to this passage.

The Wild Wood has been ‘successfully tamed’ and the middle-classes can feel safe and secure there, now they are treated ‘respectfully’ by the ‘mother-weasels’…

The denigration of working-class values can also be seen in the repeated references to Badger’s manners and forms of speech, which constantly slip outside of expected middle-class norms, and are only allowed because of who he is. This is made clear through the third person omniscient narrator, who appeals directly to the reader in Chapter Four ‘Mr Badger’ – ‘We know … that he was wrong’.

It is not only the working-classes who are attacked in this text, however. The aristocracy are also criticised, shamed and somewhat oppressed in this tale, as seen through the responses of Badger, Rat and Mole to Toad’s attitudes and exploits.

When Rat and Mole are telling Badger of Toad’s obsession with cars in Chapter Four, two things are made clear – firstly that wasting money is a Bad Thing, and secondly, that Toad is incompetent.

This plays into middle-class ideas of the aristocracy as idle and profligate wastrels, and Badger especially does not approve of this. When Badger eventually confronts Toad about his behaviour, he brings up more issues dear to the hearts of the middle-classes – reputation and rationality.

Toad must be ‘brought to reason’ to protect his friends’ reputations, and eventually, when Badger’s representations fail to induce the required rationality, he is accused of madness and locked up.

I see this as not only a denigration of the aristocracy’s profligacy, but also reminiscent of the ‘Madwoman in the Attic’ [1] – the aristocracy being feminised by a comparison with an insane female who must be locked away until she has been sufficiently subdued by masculine Reason.

At the end,

it seems that Toad has been fully rehabilitated by the middle-class characters,

he refuses to ‘perform’ in his old way and displays the proper manners.

In this book then, middle-class values are privileged over all others. From the links to the Romantic poets and their ‘cult of nature’, the suppression of the working-classes, and the ridicule of the aristocracy and their idleness, irrationality and profligacy, we are directed to see middle-class ways as ‘natural’ and ‘right’.

Some interesting links –

The Wind in the Willows animation which my kids made me watch repeatedly a couple of decades ago. The ending to this is different to the one given in the book – YouTube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ab7axFMVWa0

The Tale of Samuel Whiskers animation, where the varying sizes of the characters in the different parts of the story which Tess Cosslett mentions in ‘Arcadias?’ is much clearer than in the static illustrations of the book – YouTube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=svTvX2tkBZM

Tess Cosslett’s book, Talking Animals in British Children’s Fiction, 1786-1914, containing the ‘Arcadias?’ chapter is available online via the Roehampton library – https://capitadiscovery.co.uk/roehampton/items/873132?query=Talking+animals+in+British+children%27s+fiction%2C+1786-1914&resultsUri=items%3Fquery%3DTalking%2Banimals%2Bin%2BBritish%2Bchildren%2527s%2Bfiction%252C%2B1786-1914%26facet%255B0%255D%3Dfulltext%253Ayes%26target%3Dcatalogue&facet%5B0%5D=fulltext%3Ayes&target=catalogue

Author Jan Needle’s take on The Wind in the Willows from the perspective of the Wild Wood residents –

‘It’s 1908 and times are hard. All very well for the leisured River Bankers with their hobbies, excursions and private incomes but young Baxter Ferret has to work long and hard to support his widowed mother and hungry siblings. Baxter is a ferret with a passion. He loves engines and when his employer buys the splendid Throgmorton Squeezer lorry Baxter willingly dedicates himself to its maintenance. That’s until he meets the lunatic Mr Toad driving out of control on a dark night on the edge of the Wild Wood.’

Apologies for the squiffy numbering of the footnotes. I hope they still work!

[1] C/F Gilbert and Gubar’s text of the same name

[1] Barthes, R., (2009), in Lavers, A. (trans), Mythologies, London, Vintage

[2] https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/middle-classes-exploit-nimby-s-charter-rfrh8bg0q

[1] https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/p/picturesque

[2] Cosslett, Tess. Talking Animals in British Children’s Fiction, 1786-1914, Routledge, 2006. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/roehampton-ebooks/detail.action?docID=4817605.