First published in 1978, I was introduced to Robert Westall’s The Devil on the Road, at school in 1985. This was the first timeslip novel I had read which was aimed at young adults, rather than a child audience.

The main protagonist, and first-person narrator, is John Webster, a nineteen year old university student. Webster is very down-to-earth; he informs the reader in the first three pages that he is not a Neanderthal just because he studies engineering and plays rugby, that he loves his motorbike which he acquired through his own hard work, and that he goes looking for ‘Lady Chance’ in his vacations (p.1-3).It’s on one of these trips ‘into the wide blue yonder’ looking for Lady Chance (p.3) that John Webster finds himself drawn into the Suffolk countryside, and eventually back in time to 1647, after a series of traffic jams and breakdowns push him to take shelter in what appears to be an old barn.

In a similar way that the timeslip experience in Charlotte Sometimes is ‘resolutely linked to her very specific locality’ (Levy, Mendlesohn, p.123) – a bed in a boarding school – and couldn’t happen anywhere else, so John Webster’s slip back in time could only occur in the vicinity of this very specific ‘barn’ in Suffolk. In Children’s Fantasy Literature: An Introduction (2016), Farah Mendlesohn and Michael Levy point out this link between place or locality in timeslip fantasies, arguing that timeslip novels of the 1960s were ‘playing with Englishness/Britishness’ and engaged in ‘the construction of a previously rejected indigenous, and often localist, identity’ (p.122). Devil on the Road seems to engage in this practice, as the area around the barn is drawn in detail, in both past and present. Landscape and natural features are shown to have continuity through time, whilst also being subject to change, as seen in the circle of trees Webster witnesses ‘in their youth’ and then three hundred years later ‘the same trees; only sixty feet higher’ (Westall, p.78). The built environment is also shown to have continuity, as ‘Vaser’s barn’ is restored to ‘Vavasour’s Manor’ and the village street still exists albeit with ruins either side. The clock also ties past and present, as Webster realises in the past that ‘it was the same clock that chimed every day. Derek had told me it was four hundred years old’ (p.107). The ‘localist identity’ that Levy and Mendlesohn refer to is constructed by the villagers of New Besingtree, who despite the modernity of their shops and lives seem content to slip back into a time of ‘yarb-mothers’ and Cunning men, and a system of barter.

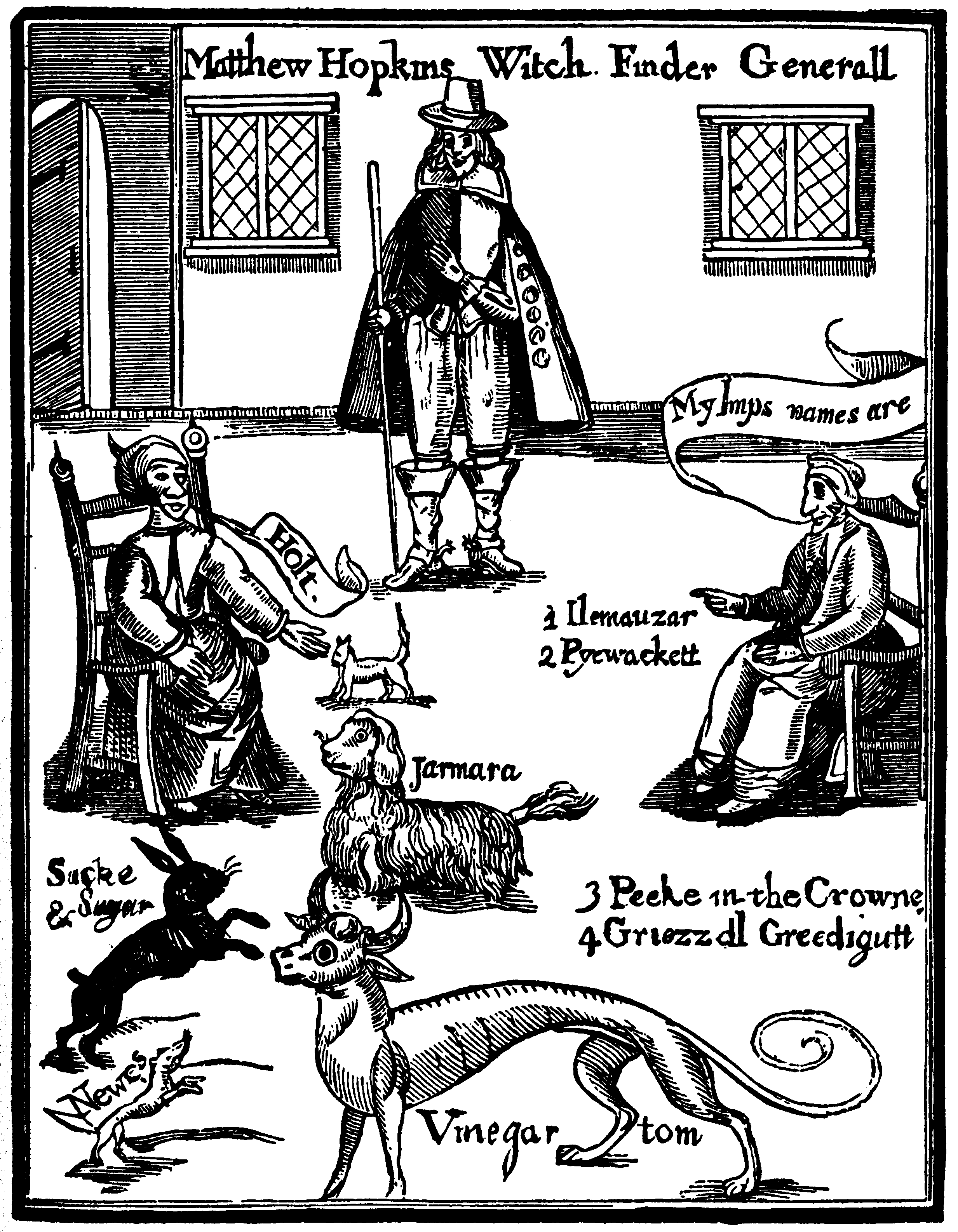

However, where other timeslip novels seem to hark back to the times in which the protagonist finds themselves, The Devil on the Road does the opposite. The world of the past that John Webster arrives in may lack the noise and smell of twentieth-century machinery, but Webster likes machinery. And when he discovers that the notorious-in-the-future ‘Witchfinder General’ Matthew Hopkins is about to visit Old Besingtree, threatening the life of the lovely Johanna, it is to modern machinery and weapons that he turns to save her life. Very little about the past is shown in a positive light, other than the landscape; Webster is exposed to filth and malnutrition, violence and death. The Witchfinder scenes are authentic – Westall draws ‘most of the dialogue’ from Hopkins’ ‘own writings, or those of his ilk’(p.247) – and frightening, making the reader as urgent as Webster to effect a rescue.

Westall clearly sympathises with the plight of the ‘witches’ in their persecution and murder, saying in his Author’s Note that ‘the social dynamics that Hopkins manipulated remain dormant in our society’ and that ‘wherever minorities exist, despised, […] and not understood, there is witch-hunt potential’ (p.248), but ultimately John Webster refuses the commitment that Johanna Vavasour needs to maintain her place in the present, and so condemns her to return to this brutal past.

This doesn’t come as a surprise, although Webster himself describes it as cowardice, as the abandonment is foreshadowed by the use of olfactory symbolism linking scent negatively to both witchcraft and seduction. Constance Classen, in ‘The Odor of the Other: Olfactory Symbolism and Cultural Categories’, writes of ‘…the association commonly made between the sexuality of the witch and her impure odor…’ (p.144) and this association is shown every time John Webster is sexually tempted by Mistress Johanna, leading to his withdrawal. When they first meet, John notices that ‘under her stiff, scratchy grey dress, her bosom swelled’, but soon notes that ‘she ponged pretty strongly […] of damp and mildew, lavender and cow-dung’ and he tries to withdraw (Westall, p.105). Later in the story, Johanna issues ‘a very sexy invitation’ by pushing her nose into John’s ear, and John is at the point of accepting this invitation when ‘the smell of her came up to me, strong. The smell of lavender and cowdung, woodsmoke and mildew’, and again he abruptly withdraws from the contact (p.199). By now, John is aware of Johanna’s actual use of witchcraft and realises that ‘every time [he] got to the brink’ of sexual activity and therefore commitment, ‘something held [him] back’ and ‘the moment [he] held her close, that old smell would come back: lavender and cowdung, woodsmoke and mildew’ (p.213). Classen points out that the ‘odor of sweet-scented flowers, suggestive of freshness and bounty, […] is generally considered attractive […] while the odor of decay, with its implications of disease and death, is generally considered repellent.’ (p.159), and in Webster’s description the sweet-scented lavender is far outweighed by the repellent cowdung, woodsmoke and mildew.

As I said, with these olfactory clues throughout the text, combined with Johanna’s manipulation of both time and John through witchcraft, it comes as no surprise when John decamps back to his modern life of motorbikes and rugger. And I think that although the text is sympathetic in highlighting the plight of the women who were essentially murdered by Hopkins for money, Johanna herself becomes something of a caricature of a witch with the combination of sexuality and bad smell, and the manipulation of men through sorcery.

References in this post

Classen, C., ‘The Odor of the Other: Olfactory Symbolism and Cultural Categories’, Ethos, Vol. 20, No. 2, Wiley on behalf of the American Anthropological Association, (1992) pp. 133-166 https://www.jstor.org/stable/640383

Jütte, R., ‘The sense of smell in historical perspective’ in F. G. Barth et al. (eds.), Sensory Perception, Vienna, Springer, (2012) pp.313-330 https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007%2F978-3-211-99751-2_18

Levy, M. and Mendlesohn, F. Children’s Fantasy Literature: An Introduction, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press (2016)

Westall, R., The Devil on the Road, Middlesex, Puffin, (1981)